Cow-Calf Commentary for Iowa Cattleman Magazine

By Sarah Phelps, ISU graduate student

April 2025

Heterosis – the most underutilized tool in the toolbox

Crossbreeding in the beef industry is possibly the most underutilized tool for production improvement. It has long been documented that crossbreeding can help improve traits from increased weaning weight to cow fertility.

What is heterosis?

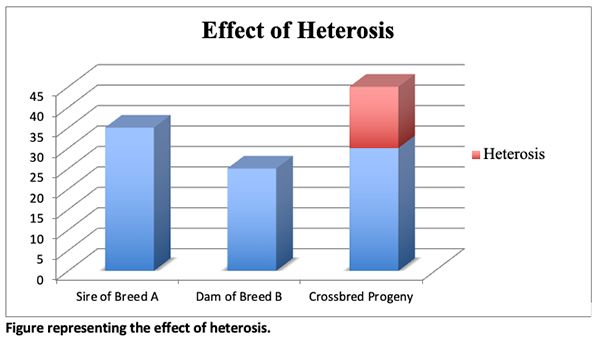

Heterosis (or hybrid vigor) is a phenomenon of improved performance for crossbred progeny over the average of their purebred parents (see graph). It results from a favorable gene combination through the heterozygosity or the inheritance of different gene versions from each parent. In contrast, inbreeding manifests the same phenomenon but results in an undesirable gene combination through homozygosity of an animal's genotype. Homozygosity refers to an animal receiving the same version of a gene from both parents. Inbreeding depression refers to the decrease in progeny performance compared to the parents. In some cases, the increase in inbreeding can result in the expression of unfavorable recessive traits through homozygosity, such as Arthrogryposis Multiplex (curly calf). Since heterosis results from increasing heterozygosity it reduces the risk of these recessive trait expressions.

The amount of heterosis expressed would depend on how distantly related the parental breeds are. For example, when crossing a black Angus with a Red Angus, the amount of heterosis will be limited. However, progeny from an Angus crossed with Brahman will demonstrate a significant degree of heterosis.

Genomics is now being utilized to estimate the amount of heterosis in an animal's genotype. It measures the amount of heterozygote genotypes in the animal’s genome and is often referred to as runs of heterozygosity (ROH). Work is now being published evaluating the amount of heterosis at the genomic level.

What traits do we see heterosis in?

Traits that express the most amount of heterosis (and inbreeding depression) tend to be traits related to reproduction and survivability. Across species we see that the level of heterosis expressed to be inversely related to the heritability. Little heterosis is observed for traits with a high heritability. Conversely, lowly heritable traits tend to show the most benefit from heterosis.

For example, research has estimated a 4.6% increase in weaning weights for crossbred calves resulting from crossing Angus with Hereford or Shorthorn. If the average weaning weight from purebred calves were 450 pounds, this would result in an average increase of 20 pounds with crossbred calves (an average weaning weight of 470).

The most economical and significant influence of heterosis is seen in cow longevity and fertility. The black baldy cow (Angus x Hereford cross) is often the poster child for reproductive efficiency because she capitalizes on heterosis. It has been well-documented that crossbred cows will remain in the herd longer than their straight-bred counterparts. If we measure a crossbred cow’s performance as the weaning weight of calves per cow exposed, the increase in production is 20% to 25%. And if you consider that, on average, crossbred cows remain in the herd longer and produce more calves in their lifetime, the contribution to operational profitability is obvious.

Breed complementary?

Every breed of cattle brings an attribute to the table and has different characteristics for production. The decision of which breeds to cross depends mainly on management and environment. An operation in Florida may cross an Angus with a Brahman for a hybrid calf that can tolerate the heat with improved carcass quality and fertility. Crossing British breeds with Continental breeds may be a better choice for operations in Iowa to improve cow longevity. When deciding what breeds to cross, the producer should consider the attributes of component breeds and they should "complement" the shortcomings of the other breed.

Why is heterosis not used more?

The simple answer is that maintaining heterosis within a herd can be complicated. Crossbreeding systems are designed to maintain a certain level of heterosis, but implementing these systems can be complex. In most cases, they need multiple breeding pastures and bulls of different breeds. This requires more thought and planning than choosing a single breed. In addition, programs such as CAB have incentivized the use of Angus cattle, but CAB does allow for crossbreeding as long as the hybrid calves meet the program requirements.

Utilizing heterosis within your cow herd can improve production and reproductive efficiency. At the end of the day, the use of crossbreeding will depend on the operation and, ultimately, how calves are marketed.

Why calving distributions matter

Your calving distribution influences production benchmarks as well as resource utilization. When considering your labor, manpower cannot be supplied economically during extended periods. Not to mention, the quality of labor is more attentive during the beginning of the season but may become fatigued and less observant as the season progresses.

Research has shown that calves born earlier in the breeding season are heavier at weaning than those born later in the season. These calves are older at weaning and have more opportunities to reach a heavier weaning weight. When these calves are followed through the feedlot, the earlier born calves had heavier carcass weight and more choice or prime grades than calves born later in the calving season. In addition, heifers born early in the calving season have been shown to have a higher pregnancy success rate and remain in the herd longer. These heifers are set up for success as they are older and heavier at weaning, older at breeding, and are more likely to be cycling by the first day of the breeding season. Heifers who calve in the first 21 days of a calving season, are more likely to remain in the herd longer than those who calve later.

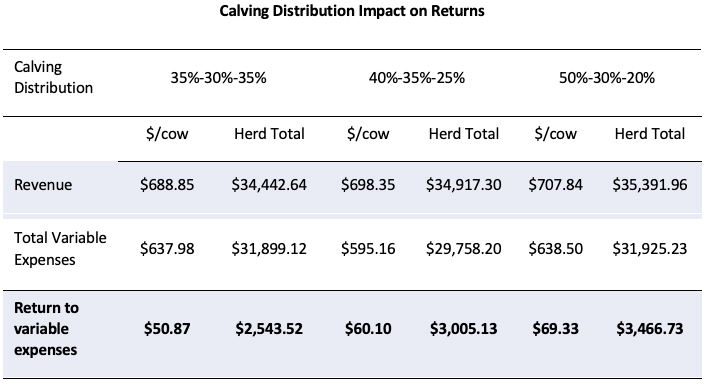

The economics of calving distributions have been well documented. A group from the University of Tennessee conducted a simulation looking at the impact of calving distributions on financial return when calves were sold at weaning. They found a $18.46 per cow improvement when the calving distribution was improved from 35% born in the first 21 days to 50% of calves born.

Reviewing your calving records can help you determine your calving distribution and if adjustments need to be made. It is also advisable to analyze your calving distribution by dam age, as this can highlight any specific age group of cows that may be calving later than expected, providing insight into how to address the issue.

Management considerations

Your calving distribution is a direct result of your breeding season. For mature cows, most breeding seasons are 60 days, allowing for the potential of 3 estrous cycles. Heifers are often exposed to a shorter breeding season of 45 days, which places selection pressure on those heifers who cycle and breed earlier in the season. Maintaining a defined breeding season ensures your cows calve within a set time window.

As you transition from calving to breeding, consider the nutritional status of your cow herd. Maintaining your herd at a body condition of 5 to 6 is optimum for reproductive performance. Cows in poor body condition going into the breeding season can delay their ability to get pregnant, which results in later calving.

If your calving distribution is not ideal, estrus synchronization is a great tool to help consolidate and move your calving distribution up. Estrus synchronization can be used with artificial insemination (AI) or natural service. Multiple protocols can be utilized, and the Beef Reproduction Task Force is a great resource to compare protocols. When considering a protocol, consider your resources, such as labor, not only at breeding but also at calving time.

2025 Archives

2024 Archives

2023 Archives