Growing Beef Newsletter

January 2025, Volume 15, Issue 7

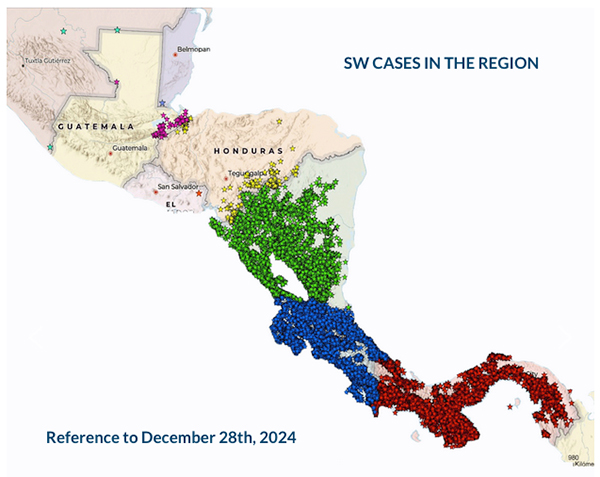

Screwworm Update

Matt Brewer, associate professor, ISU department of veterinary pathology

Primary screwworm is the larval (maggot) stage of one species of fly (Cochliomyia hominivorax). The reason primary screwworm is a major concern is that the larvae can feed on living tissue, whereas other fly larvae only feed on dead tissue. Primary screwworm female flies lay eggs on existing wounds, which can be as small as a scratch or a tick bite, and any warm-blooded animal can be a host. Eggs hatch into larvae and burrow into living flesh for up to 7 days before exiting the wound. Larvae burrow into soil, pupate, and hatch weeks to months later. As more flies hatch and lay eggs, the larvae feed causing deep cavitation into the muscles and can kill an animal in about 10 days if infestation continues. Sites of wounds from castration, ear tagging, or scrapes from barbed wire are susceptible.

Also known as “new world screwworm,” these flies historically occurred in North and South America. In the 1950’s, the USDA began a clever strategy to aggressively eradicate primary screwworm. The premise of the program is that female flies typically only mate a single time in their lifetime. If the female breeds with a sterile male, the offspring are non-viable. Researchers developed an irradiation method for generating massive numbers of sterile males that could be distributed via airplanes into infested areas.

The USDA declared that primary screwworm was eradicated from the United States in 1966. From that time until the present, the USDA has worked with several Central American countries to continue the sterile male fly technique, successfully eradicating primary screwworm southward such that in 2006, a new fly production facility was built in Panama to create a barrier between Panama and Columbia in order to keep Central and North America Screwworm free. Up until recent years, new world screwworm was thought to only occur in South America and in some Caribbean islands.

In 2016, primary screwworm was discovered in deer in the Florida Keys. Using the sterile insect technique, it took about seven months to declare screwworm eradicated on the islands. Interestingly, the official USDA unit in charge of visually identifying maggots at ports of entry is at the NADC in Ames. Screwworm eradication is among three parasitic diseases that are line items in the federal budget.

In 2023, there was a reemergence of screwworm in Panama, followed by discovery of thousands of cases in other countries. In December 2024, Mexican authorities announced they had discovered three cases along the border with Guatemala. This prompted USDA to suspend shipments of cattle across the US-Mexico border. There is no doubt that this development has had an effect on cattle prices. Trade can only resume pending construction of facilities where USDA personnel can inspect and treat cattle prior to entry into the United States.

Affected birds and mammals exhibit the presence of wounds that grow in size with maggots present and often smell decayed. Although unlikely at this time in Iowa, the screwworm larvae can be submitted through a veterinarian and identified at the ISU Veterinary Diagnostic Lab. Producers should also be aware that reopening the border is likely to have an effect on the cattle market.

Image by the Panama-United States Commission for the Eradication and Prevention of Screwworm (COPEG)

This monthly newsletter is free and provides timely information on topics that matter most to Iowa beef producers. You’re welcome to use information and articles from the newsletter - simply credit Iowa Beef Center.